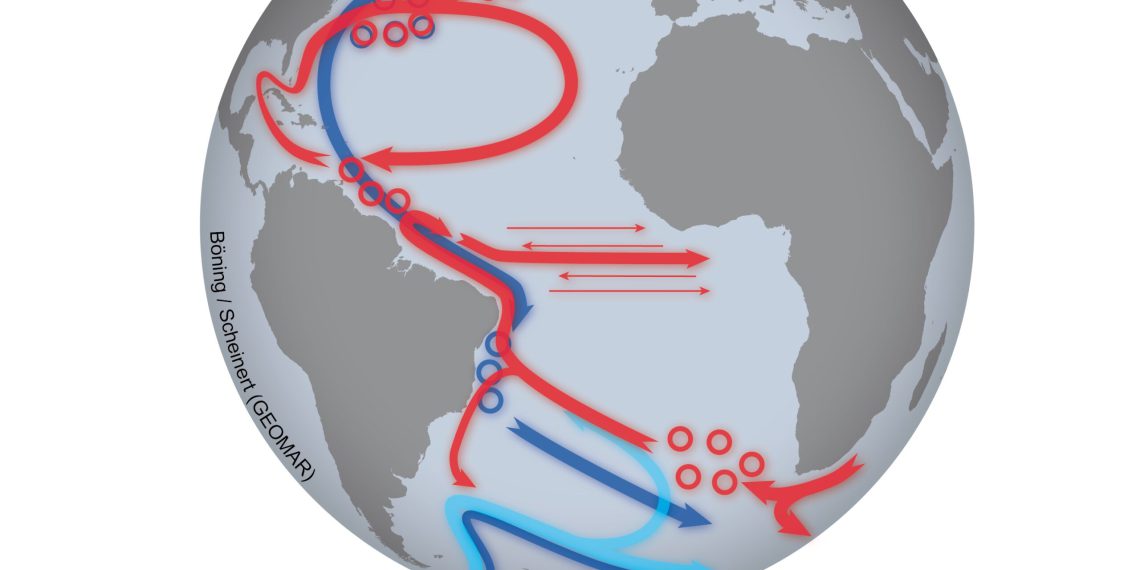

In a publication in the journal Nature Climate Change, researchers from Kiel once again contribute to the understanding of changes in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation — known to the public as the “Gulf Stream System”. It is just as important for the global climate as it is for climate events in Europe. The research focuses on whether human-induced climate change is already slowing the oceanic overturning circulation. According to the new study, natural variations still dominate. Improved observation systems could help detect human influence on the current system at an early stage.

Is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) slowing down? Will this system of ocean currents, which is so important for our climate, possibly come to a standstill in the future? Are the observed fluctuations of natural origin or already a consequence of man-made climate change? Researchers from various scientific disciplines are using a wide range of methods to try to better understand the gigantic oceanic overturning movement.

“The AMOC provides mild climate in Europe and determines seasonal rainfall patterns in many countries around the Atlantic. If it weakens over the long term, it will also affect our weather and climate. It could also cause sea levels to rise faster on some coasts and reduce the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide and mitigate climate change. We depend on the AMOC in many ways — and yet so far we can only guess how it will evolve, and whether and how much we humans ourselves will drive it toward a tipping point where an unstoppable collapse runs its course.”

- Professor Dr. Mojib Latif, Head of the Research Unit Maritime Meteorology

Using evaluations of observational data, statistical analyses and model calculations, a team led by Professor Latif has therefore examined changes in the current system over the past one hundred years in greater detail. The researchers have now published their results in the journal Nature Climate Change. According to the results, part of the North Atlantic is cooling — a striking contrast to the vast majority of ocean regions. The analyses indicate that natural fluctuations have been primarily responsible for this cooling since the beginning of the 20th century. Nonetheless, the studies point to an incipient slowing of the AMOC in recent decades.

Climate models consistently predict a significant slowing of the current system in the future as our carbon dioxide emissions continue to rise, the ocean continues to warm, and the melting of Greenland ice accelerates. “Our results confirm earlier scientific findings. But the question remains how long we will remain in the realm of natural variability and when climate change will take control of the AMOC. Then the trend would only be in the direction of weakening and risks could increase significantly,” emphasizes Dr. Jing Sun, meteorologist at GEOMAR and co-author of the study.

Better observational data are needed to determine the critical limit, the authors conclude. “If we systematically and permanently measure the changes already taking place in all regions of the Atlantic, we will also be able to say with greater certainty what influence climate change has on the AMOC current system today and in the future,” says Professor Dr. Martin Visbeck. The head of the Physical Oceanography research unit at GEOMAR is also co-author of the publication. “We don’t see any sure signs at the moment that the system is slowing down dramatically — rather, it is fluctuating. But since the latest climate models agree that a significant reduction will occur, we should know how much longer we’re on the relatively safe side of natural change.”